Seven minutes of my life are missing.

All is black.

All is silent.

There is no consciousness, no awareness, no realisation of unconsciousness. It is silent, amorphous, a world without verbs or adjectives.

None are possible.

They don’t exist.

Neither do I.

“Hello ! Can you hear me David ?”

I do not respond.

“Can you hear me David ? Do you know where you are?”

There is a bemused look on my face. I still don’t respond.

“Lie down David and try to relax, we’re here to help you”

Reality seems strange, it’s as if I am now dreaming, but dreaming in black and white, a fuzzy black and white. I can hear people speaking but the words make no sense to me. I am sitting on the tiles by the side of a swimming pool clothed in just my swimming trunks, my goggles are on my upper arm. I am surrounded by people. Some are in their swim wear, some clothed.

Reality disappears.

It returns.

The ceiling and lights fade in from nowhere, colour partially restored. I look across the swimming pool. What am I doing sitting here when I should be swimming? Pain is searing through my rib-cage, its intensity changing with each breath. Confusion still overcomes me.

Sleep.

I need to sleep.

I need to finish this dream.

I want to wake to the proper reality.

Someone is kneeling, looking at me, talking to me. He is wearing green. His mouth is moving, words are escaping and traveling towards my ears. They fail to gain entry. I have lost the ability to comprehend.

Unconsciousness engulfs me, the dream has disappeared and I see the blackness of nothing. I have returned to my world devoid of verbs and adjectives.

Time has no meaning in my world, for tracking the intervals of a clock ticking would require consciousness and perception and I have none. Instead I exist, yet do not exist, in nothing.

I am awake, I can see reality in faded colour, a fuzzy TV picture.

I am lying down.

I am outside.

I am talking, conversing.

I am asking why the road is so quiet.

This is London, in place of the rumble of traffic there is only silence.

This is not normal.

The police have closed the road.

Reality is proving to be unreal for me. I want sleep again.

A solitary vehicle moves, twists, turns, then lurches forward.

A destination beckons.

A blue light flashes.

A siren sounds its signature.

I fall into a deep sleep.

My slumber, if it could be described as such, recedes and a reality returned to me. I am warm and comfortable, lying in a bed. I open my eyes and the ceiling comes into view. A cannula protrudes from my right hand, another in my forearm, the latter being attached to a thin plastic tube, a bag of colourless liquid is feeding its content into my arm. My chest is littered with small electrodes, each attached to a coloured cable, the monitor above my head absorbing their signals. Below my right collar bone sits a large white rectangular pad, another identical pad covered my lower left ribs, their significance not apparent to me.

As if from nowhere a man appears, he is dressed in light green cotton, a mask is around his neck, then a second similarly attired person joins him.

“Hello. How are you feeling ?”.

Yet again I am confused. Someone replies, it sounds like my voice, the words are coming from me, but I am not conscious of having decided to speak. I want the voice to stop so that I can reply.

“Err. I feel….err.…”

The voice sounds in synchronicity with my desire then stops. I start to speak. The same voice appears and I realise that it is mine, that I am in control of it, that I am providing the words

“Where am I ? What am I doing here ?”

The first man dressed in green speaks, his terminology medical.

“Well, you are a very lucky man. You had cardiac arrest after your swim. We checked you over, one of the arteries on your heart was narrowed, not occluded, so we put a stent in it as a precaution. Unlikely to cause and arrest, but then you presented as such. How are you feeling?”

My humour returns

“Well, I have felt better. My ribs hurt. It feels like I have been hit with a sledge hammer”

“That would have been the CPR, often ribs are cracked during chest compressions. A small price to pay, wouldn’t you agree”.

My reality has just expanded. Cardiac-arrest and now CPR.

“It’s hard to tell if you had a heart-attack or not but you certainly suffered cardiac arrest and it looks like they did two rounds of CPR on you and then one shock from a defibrillator. You were extremely lucky as it looks like the gym staff were well trained and had a defibrillator and knew how to use it”

My comprehension of the events of the previous hours are clouded by morphine and Medazalam. His words seem unreal to me, they drift around my mind until finding refuge from the medication and I can understand their meaning. As the morphine induced warmth returns to my mind I smile as I reflect on the medic’s words.

I question myself, the internal dialogue within demanding answers. I nearly died, my heart stopped beating, someone resuscitated me, someone revived me.

Where did this all happen ? Who saved me ? How did I get here ?

Medication applies its benefit once again and I slip into a warm and delicious

sleep.

The day had started just like any other ordinary day via the shrill tones of mybedside alarm clock at 05:35. I slipped into my standard routine of exiting my

bed and occupying the shower for some all-too-brief minutes. Showered and shaved I descended the stairs to my home office, where in a built-in cupboard resided my shirts and suits. I selected a white shirt, double-cuffed, gleaming resplendently on its hanger and I slipped into it. Alongside the shirts sat my suits, depending on which one was worn the previous day would determine my choice for that day, I selected my favourite navy Ede and Ravenscroft two-piece, and lowered myself into the trousers. With my tie affixed and shoes placed on my feet I pulled on my jacket and exited the house. I was expecting an ordinary day at work (although I was still excited from the previous evening event’s where I had played on stage in a band for the first time ever, my skill on guitar and vocals exceeding everyone’s expectations).

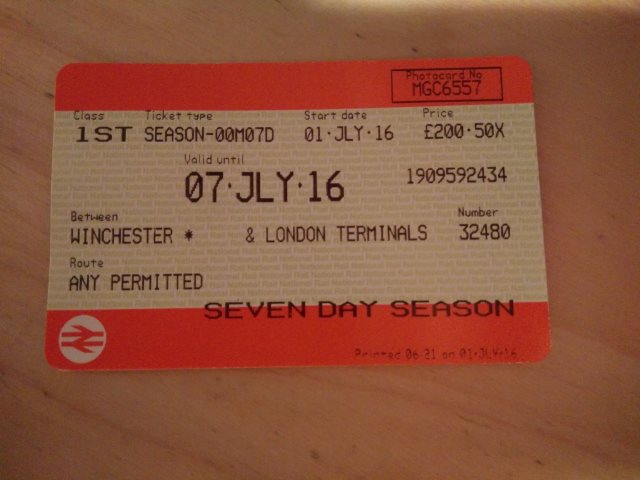

The morning was fresh, long shadows of the low sun greeted my train on its journey to London. The spires of city came into site as my carriage slid through the southern suburbs, my destination of Waterloo station approached. After a brief subterranean transit I was deposited in the heart of the City of London, within minutes I was sitting at my desk on the 7th floor of a stone office building. Bag and jacket deposited I descended in the building’s lift to the basement.

Breakfast had beckoned since the first tone of my alarm clock and I wanted to diminish my hunger pangs. Satiated I began my tasks for the day. It was 07:45.

Work was intense that morning, a deadline was approaching and it required concentration and the minimisation of office distractions. Caffeine fuelled me as my hands and mind crafted solutions to the problems that presented themselves.

Without acknowledging the passage of time midday arrived, then bypassed me.

At 12:30 my concentration departed as I was presented with a dilemma: should I get some food or leave the office for a lunch-time swim. After briefly pondering the options I grabbed my rucksack and exited the building, moving in the direction of the swimming pool.

Exercise was important to me, I am not a naturally gifted athlete, built for power not speed, but through hard work and determination I had mastered a number of sports. Two marathons had been completed, a tattered belt of black was slung around my waist in my weekly karate sessions, three times a week I would plough through 500m with a combination of breast, front-crawl and butterfly strokes. I felt in good shape, my physiology outstanding.

Sliding behind the Royal Exchange I passed the Bank of England and descended the steps to the basement of a building which contained my gym and swimming pool. At reception I joked with one of the receptionists then entered the changing room where I removed my attire, placing my suit carefully in a wooden locker. I slid into my black trunks, placed my goggles on my arm and extracted my padlock from my rucksack, using it to secure the locker with a resounding click.

The key to the lock sat on a small carabiner, I threaded the waist cord of the trunks through it and secured both with a loop and a bow. From a pile of freshly laundered white towels I selected one and descended some steps and entered a corridor leading towards the pool. Mid way in my journey I entered a small tiled enclave and let the deliciously warm water of a shower cleanse my body. Shower completed I skipped up three long steps and walked alongside the pool to the end, nodding to the life-guard.

The pool was calm, two lanes were occupied, and, unusually for lunchtime, the fast lane was empty. My breast-stroke swimming style is strong not elegant and could not be described as quick, however, this lane was free, I would use it. I dropped from the end of the pool into the warm water, affixed my goggles and began my 500m. The swimming was tough, some days I glide, some days I struggle, that day in it was the latter.

500m approached and I switched to my least favourite stroke of front-crawl. Finishing with a flurry I rested at the end of the pool then pulled myself out. The air above the pool area was hot, it was a sweltering day outside. I moved to a recliner at the side of the pool, I wished to calm my breathing, to cool down, to relax before taking a shower and the return to work in my suit.

I lay on the recliner for some minutes relaxing, my eyes were half closed and my pulse and breathing slowed towards normal.

And then it happens.

Nothing outwardly dramatic, nothing painful, nothing noticeable to others. I open my eyes and tilt my head to look at my chest, it feels as if something has broken inside, like a rubber-band snapping. A ripple of panic overcomes me, I know I am in trouble, that mortal danger is close, that desperate measures are required.

I am dying.

In one last act, one last final push, the last thing I do, the last thing I am capable of doing, I pull myself up from the recliner, hands clasped to my chest and attempt a scream. The world fades. Reality disappears. I fall backwards across two recliners, my body motionless.

My heart has stopped beating. I am unconscious. I am close to death.

Panic ensued.

People ran to me, help was summoned. Gym staff appeared, one takes charge.

I was lifted to the floor and rolled into the recovery position, a sensible move.

Yet I was not breathing. My heart was not beating.

The gym staff member in charge sensing this then rolled me onto my back, pushed his hands together over my breastbone and began compressions, squeezing my chest, forcing my blood to circulate, keeping me alive.

One round of CPR complete he rolled me back to the recovery position, I appeared to be breathing. I wasn’t. This was agonal breathing, a brain-stem reflex. A pre-cursor to death. I began to turn blue. The cyanosis of oxygen starvation. I was rolled onto my back and CPR commenced for a second time, my chest bending in response to the compression, my ribs cracking under the pressure. I was being kept alive.

A defibrillator appeared. Its rectangular white pads were unpacked and attached to me; one on my upper right chest, the other to my lower left rib-cage. A button was pressed and the automated device took over. People moved clear.

A shock is delivered.

My body jolts.

My attendants hold their breath.

Watching.

Hoping.

Willing the shock to work.

My chest moves.

My heart beats.

I am alive.

I would not have survived the events of the 7th July 2016 without the

intervention and tenacity of a number of people to whom I am eternally grateful.

The first on the scene was a member of the gym staff and he took charge of the situation, performing CPR and using a defibrillator on me – I would not be alive without him or his swift actions. I owe him a debt I can never repay.

The other members of the gym played their part in saving me, I cannot underestimate their contribution nor thank them adequately.

The paramedics who attended, their outstanding care, their expert diagnosis and transportation of me to the best heart-centre in London meant I suffered few after effects. I cannot thank them enough.

The doctors, nurses, hospital staff, cleaners, cooks, receptionists. I owe them so much.

The London Ambulance call handler who took the 999 call, who saw through the panic, who realised something was seriously wrong. Thank you is too trivial a phrase.

There are other people who played their part that day, people I was not aware of, am not aware of now.

To all of you I owe a debt of gratitude.

To all of you I owe my life.

Physicist, software developer, CFR, lifesaver, SCA survivor

2 thoughts on “Seven minutes”